The eye is one of the most important senses. Nearly 80% of information about the surroundings is delivered to the brain by the eyes. The answer to these questions may be eye-tracking. It is a research technique that allows us to follow the eye movement of the subject in specific settings. There are a few techniques, but video eye tracking is the most common, non-invasive procedure. It follows the eye movement based on the reflection of infrared light from pupils. The computer/software uses calibrations to learn how the subject’s eyes move on the screen. It adjusts to the light in the room and any lenses the participants might have, which allows scientists to show subjects different stimuli, videos, or photos and conduct studies with a simple click.

Nevertheless, it was not always as easy; one of the first ideas of eye-tracking dates back to the 19th century. Louis Emile Javal, a French ophthalmologist, conducted the first experiment on reading in the 1870s( Płużyczka, 2018). The scholar placed the mirror on the book pages. When the participant was reading, the experimentation stood behind him and tracked the eye movements by hand. It was a far less precise experiment than today’s technological advancement, but it created the fundaments. What was innovative about this research was that it showed that reading is not a linear process. It consists of saccades, short rapid jumps of the eye, and fixations, the „stops” of the eyes in one place. When the fixations occur, we shift our attention to this specific place. Researchers continue to use this terminology today, but now we know that the eye never truly stops. It can concentrate in one place but still create small movements. If we stop the eye artificially, we will acutely lose vision.

Our view area contains central vision – the sharpest image, where we fixate- and parafovea, the second layer of our vision, located 5° from the center of fixation. The last layer is peripheral vision allows one to orient in space. When reading the text, saccades move our fixations to the longer content words than function words. 2-3 letter words are only fixated around 25% of the time because we register them with parafovea. In contrast, words eight letters or longer are almost always fixated (and often fixated more than once) (Rayner,1998). Research on reading plays a huge role in preparing educational materials for students and teachers. These results represent just one type of research conducted via eye-tracking. Possibilities are endless, starting from analyzing the perception of paintings in the museum and ending with conducting experiments in virtual reality. (Read more about conducting the study in RealEye)

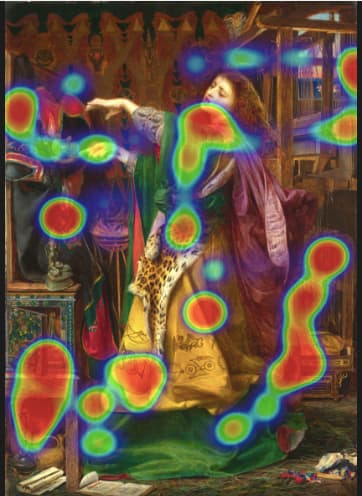

Nevertheless, to analyze the eye-tracking data, researchers created specific tools to show how participants in the study perceived the stimulus. One representation of data creates scan paths, where the circles correspond to the fixation and the lines to the saccades. Based on this analysis, researchers can see how the eyes move on the image step by step and where the most fixation occurs. Another way to illustrate the data are heat maps, where the intensity of the color corresponds with the number of fixations in a specific place. If researchers are interested in quantitative eye movement measures, they create an area of interest (AOI). By appointing an AOI researcher can perform additional statistical analyses, such as time to first fixation – how fast we are looking at a particular area for the first time. As well as the number of fixations/gazes, how much time participants spent looking at this area, and ratio – how many viewers looked at this area at least once.

All these analyses answer the questions posed by researchers, wherein are the images the most fixations from subjects? What kind of manipulations can we use to make people look where we want them? A pioneer who studied the differences in image perception depending on the task given to the subject was Al’fred Luk’yanovich Yarbus (read more). In his book „ Eye Movements and Vision,” Published in 1967, he describes an experiment where he was showing the same painting Ilya Repin’s „The Unexpected Visitor,” to subjects giving them a different task to focus on during the perception of the painting. Each recording lasted 3 min. Yerbus asked some participants to examine the photo without any mission ( free examination), others to estimate the family’s material circumstances family in the picture or to remember the position of the people and objects in the room, or even to estimate how long the unexpected visitor had been away from the family. Yarbus’s study results showed that with each different task, the perception of the painting was changing. It created a specific perception cycle, similar to people given the same job.

From nowadays perspective, this knowledge is on when it comes to neuromarketing to understand how we can create advertisements so that they are more effective for the product is better displayed and eye caching. Eye-tracking research is developing rapidly. As mentioned, there are many topics for research, and a well-planned study can show interesting results, not only in the field of neuromarketing but also neurorehabilitation, neuroscience, education, and many others. (To see more interesting articles)

Bibliografia:

Płużyczka, M. (2018). The first hundred years: A history of eye tracking as a research method. Applied Linguistics Papers, (25/4), 101-116. doi:10.32612/uw.25449354.2018.4.pp.101-116

Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 372–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372

Tatler, B.W., Wade, N.J., Kwan, H., Findlay, J.M., Velichkovsky, B.M.,(2010). Yarbus, eye movements, and vision. Iperception. 2010;1(1):7-27. doi: 10.1068/i0382.